How did an American-educated Belgian’s passion for gothic churches, remote sensing, and building engineering create a plan that would help save a Parisian icon?

Since its inception in 1163, Notre-Dame de Paris cathedral survived invading armies, homegrown revolutionaries and, in more recent times the visits of millions of tourists.

Longevity like that develops a sense of invulnerability: when life was difficult, Parisians could glance up at ‘Le Fleche’ nearly one hundred metres above them and understand that survival is always possible.

So when in 2019 fire burnt through the forest of oaks that had supported that spire for so many centuries, solidity and support was replaced with shock and sadness.

The damage was extensive – €840m was eventually raised in the appeal – and debates as to why, when and how this Parisian icon should be rebuilt raged through the nation and far beyond the borders of France.

Recreating this lost architectural masterpiece would rely on talented and experienced building engineers and the rare skills of artisans. But, if their combined efforts were to be effective, they would need to know exactly what they were building back.

The heroes of this problem emerged through a lineage of academic enthusiasts who combined their love of Gothic buildings with an inspired use of technology.

This is the story of how the culmination of their work led by an American-educated Belgian musician who died at the age of 49, only a few months before the blaze on the Ile de la Cité, left a priceless blueprint of this famous church.

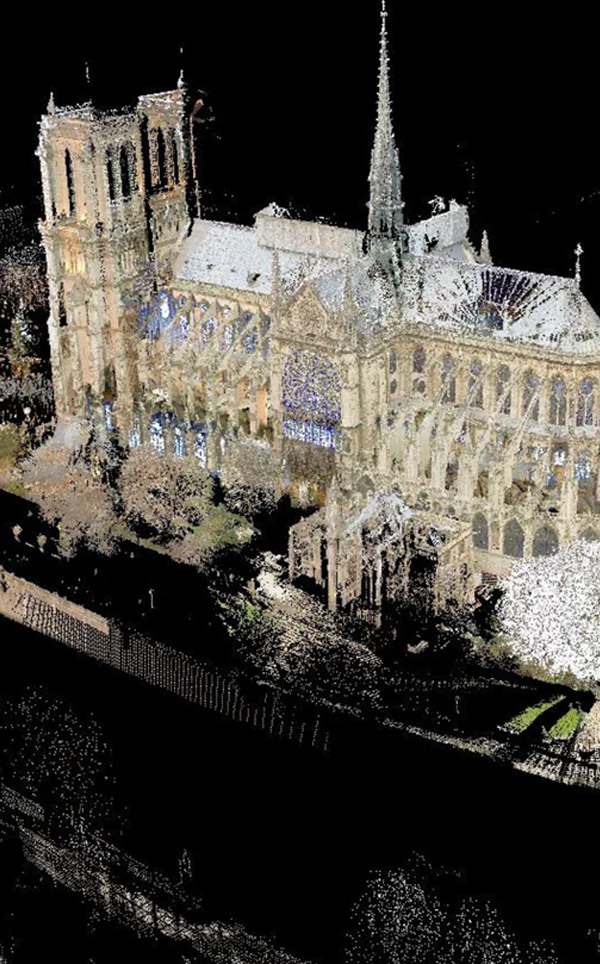

Notre-Dame de Paris in Paris, France

Image source: Freepik

Andrew Tallon photographed scanning the Washington National Cathedral in 2014.

Photo: Vaser WNC 2014/ Craig W. Stapert.

Born in the Flemish city of Leuven, Andrew Tallon lived in Paris as a young child, walking past Notre-Dame on his way to school. In his own words he became ‘obsessed’ with the place. How did anyone build such an outsized building on such narrow walls, especially as they were more stained glass than stone, and how did they do it nearly a millennium ago ?

When his family moved to Wisconsin, Andrew attended the local high school before being accepted to Princeton University, to study for a Music degree. Whilst music was the day job, Andrew spent every spare moment he had with his first love of gothic architecture and as luck would have it, Princeton provided him with access to a building engineering pioneer.

Professor Robert Mark, taught at Princeton for 34 years during which time he founded the Program in Architecture and Engineering. Prof. Mark carved his niche by using the latest computer-based modelling techniques of his time to uncover the history of buildings and their construction.

His experiments delivered previously hidden insights into how Istanbul’s Hagia Sophia, the Parthenon of Greece and some of the World’s largest gothic cathedrals were built and remained standing.

Carolyn Marino Malone, Professor of Art History at the University of Southern California and Mark’s colleague recalled that: “He used technology for the first time to offer a scientific method for evaluating the structural reasons for the invention of Gothic features.”

The technology Malone referred to was photoelastic modelling – the way materials (including masonry stone) reflect and absorb light under mechanical deformation – and holographic interferometry – an extremely accurate method for measuring movements in materials under stress. The features he helped to explain included flying buttresses.

Andrew Tallon devoured Professor Mark’s teachings: somehow he attended every single one of Mark’s lectures during his time at Princeton. Leaving music behind, Tallon needed to know more and so went on to study, first for an MA at the Sorbonne in Paris and then a PhD at New York’s Columbia University’s Department of Art History under Professor Emeritus, Stephen Murray.

In 2007 and now a professor himself, Tallon was working at Vassar Art College in New York State where he and Professor Murray were funded by the Mellon Foundation to develop the website: Mapping Gothic France.

That project saw Murray, Tallon and a team of enthusiastic undergraduates visit and scan churches in France (and some in Britain) to build up a library of virtual tours through these buildings, each accessed via their location on the online map.

You can explore it yourself at: https://mcid.mcah.columbia.edu/art-atlas/mapping-gothic/map

The project included Tallon’s beloved Notre-Dame and starting in 2010, he and his colleague Paul Blaer, photographed and scanned both the outside and inside of the church with a LiDAR sensor.

LiDAR, which stands for Light Detection and Ranging (if you add the i) is a remote sensing technique that captures the reflections of laser pulses (detection) to calculate the distance (ranging) to the object they are looking at.

Do that a billion or so times (creating what is known as a point cloud), use some pretty nifty software and voila! You have a virtual, measurable three-dimensional model of your building, road, town, mine, field, well you get the idea.

LiDAR is also the technology that lets autonomous vehicles ‘see’, even if Elon Musk isnt a fan. Given that light always moves at well, the speed of light and few vehicles travel at 186,000 miles per hour, there is easily enough time to build models of everything that is around a car, tractor, dumper truck, well you get the idea, and move the vehicle accordingly.

With stationary objects, even one as complicated as a cathedral, a model created with a billion points allows the viewer to measure distance between features, monitor changes and in the case of Tallon’s model of Notre Dame, be used as a scale reference that can guide the rebuilding process.

It maybe, given his accumulated knowledge, that Tallon had already suspected that something was wrong but with the survey complete, he was concerned enough about the stability of Notre-Dame to write to the archbishop of Paris and demand that renovation work start as soon as possible (ironically, it was during that renovation work that the fire started but before we start blaming Tallon it is worth knowing that many of the irreplaceable statues that had looked out over Paris for so many years, were in storage and thus saved).

When the rebuilding work restarted, “[Tallon’s] scan enabled us to reconstruct the vaults without any hesitation from a dimensional or formal standpoint, and it also granted us total freedom to understand how [the cathedral] was made, to be able to rebuild it in a thoughtful, intellectual, and intelligent way,” said Philippe Villeneuve, Architect-in-Chief of Historic Monuments in charge of Notre-Dame.

His partner also in charge of the restoration Pascal Prunet put it more poetically: “Andrew Tallon’s point cloud, well, it’s a bit like listening to a Mahler symphony, it’s a recording, but one that needs to be decrypted.”

Due to the efforts of the leadership team of Villeneuve, Prunet and Remi Fromont and all the people who worked on restoring Notre-Dame, the people of Paris have their sense of longevity back.

One wonders if there is space on a wall somewhere to remember the remote sensing application expertise of Marks, Murray and Tallon.

There should be.